19th Century

James Hogg - In June 1803, writer James Hogg “The Ettrick Shepherd” passed through, travelling down Glen Sheil, to Loch Duich, over the hill to Strome Ferry, and on to Lochcarron. His account is interesting reading about the area in general, but he says little about our immediate area. “The whole [of Lochalsh] is an excellent pasture country, and excels all that I visited in the whole western coast of Scotland and the Isles, for it’s richness of pasture, if we except some parts of Skye. …Loch Duich is an excellent fishing station, but there are neither villages, roads, bridges, nor post office in the whole country. The gentlemen employ a runner to Loch Carron, where a foot post arrives once a week from Inverness by way of Strathconan, where he must often be detained by storms and flooded waters..”

“I came in upon Loch Carron at the narrowest place, nigh where it opens to the sea, when there was a boat just coming to land, freighted from a house several miles up on the other side of the loch, by some people bound to the place from whence I came. I waited their arrival thinking it a good chance, but in this I was mistaken. No arguments would persuade them to take me along with them. They alledged that it was depriving the ferryman of his right. But effectually to remove this impediment I offered them triple freight, but they dared not to trust themselves with such a sum, for they actually rowed off and left me standing on the rocks, where I was oblidged to bellow and wave my hat for no small space of time. The ferryman charged sixpence and a dram of whisky.”

People, Population and Ruins

In the 18th and 19th centuries large numbers of people left the highlands, some because of economic circumstances, but many evicted by landowners in the notorious “clearances” to make room on the land for more profitable sheep farms, and deer ranges. The result is a landscape scattered with ruins, although many have very little left, as the stone would have been used for other buildings, walls etc.

Sir Hugh Innes - In 1801 Elgin sheep farmer Sir Hugh Innes (1764-1831) bought Lochalsh, and in 1807 he had his land mapped by John Blackadder. The result is the first really accurate map of the area, and in 1812 he had lines drawn onto the map to divide the land into areas which could be let as sheep farms: Fernaig, Braentra, Auchmore, and Ardnarf. Evictions started immediately.

Population statistics, available from census returns, reflect these movements. Inland areas such as Braeintra and Glen Udalain were depopulated in the early 19th century, at the same time as the overall population was coming towards its maximum (around 1830). People were initially moved to coastal crofting settlements such as Ardnarff and Portachullin, which showed a dramatic population increase. As large numbers of people left the area for places such as Canada, USA, Australia as well as other parts of Britain, the overall population steadily declined from then until the 1970s, when it eventually started to recover. Strome ferry went against the trend for a few years in the late 19th century, when it was an important port connecting the isles to the railway.

Braeintra - Ruins have been found in the plantation and the hill behind Braeintra, and there is said to have been an inn somewhere here. An old ladle was found there some years ago. NG861318 approx.

Two hundred years ago the village of Braeintra was at a site which is now in the plantation up the Glen, (on the south side, NG 876325). The 1st edition OS map (1875) has 8 ruins, but in 1807 they were inhabited, and the 5 buildings shown are labelled “Braentra”. When the sheep farm of Braentra, named after the village, was created and let, a farmhouse was built at the site of the present Braeintra (Riverside cottage), along with the steading. Around the same time, the residents of the old Braentra were cleared to coastal areas such as Camuslongart and Portachullin, and the name became associated with the place where the farmhouse had been built. Braentra is listed in the 1892 Royal Commission (Highlands & Islands) as having had 7 tenants in 1798, but does not appear at subsequent dates.

There are also two small ruins on the north side of the Glen, marked on the 1875 OS map, perhaps shieling huts. NG 873332

Portachullin and Fernaig -

According to Roderick MacRae (Napier Commission Report 1883) the first people came to Portachuillin (from Kyle) in 1813. MacRae himself had come from Sallachy in 1828. By 1851 the population was 72, today three houses are inhabited, and there are many ruins.

The Napier Commission toured the Highlands taking statements from crofters and others to investigate the ongoing unrest at the situation. It resulted in the crofting laws being passed in 1886. Roderick MacRae’s statement to the commission gives a picture of the situation at the time: “…we are so confined by the nature of the place and by fences and otherwise, that it is impossible for the small plots of land which we have to support the number of tenants (8). Our houses are of the most miserable description, and they are built so close to the sea that in tempestuous weather there is a considerable danger that the sea may enter them. We keep two cows each and their followers, but owing to the smallness of our allotments, we have to pay from £8 to £9 in the winter season for their keep.” He goes on to say that the quality of the land is deteriorating as the seaweed they are allowed to use has to be cut out at sea, at five fathoms. However in later questioning he says that they have been recently allowed to take it from the shore.

He continues: “We can’t make any meal from the oats growing on our ground, as it is barely sufficient to sow the ground next year. With the exception of potatoes, the produce of our grain crops is not much more than what we sowed.” “Thirty-seven years ago [in 1846] the hill pasture of Altegre [Allt a ‘Ghraighfhear NH085380, near Loch Monar] on which we could graze about eighty sheep, was taken from us and converted along with other tracts into a deer forest. We would consider ourselves very well off if we had land enough to support four horses between us all, in addition to the cattle we have already. The caschrom [foot plough] which we have to use in turning the soil does the work but very imperfectly, and by the difficulty and slowness of the work we spend a great deal of valuable time, which would be greatly shortened if we had horses.” MacRae was asked if they build their own houses; “I was building a house and the proprietor helped me to do it. There was only one other man who improved his house, and the proprietor gave him wood and lime, and the man slated it at his own expense.” When asked if they fish at Portachullin he replied “ yes, we must live somehow”. He considers that “four families might be comfortable enough in the place”. There were eight tenants, and seven families who were paying no rent. The 1891 census shows 11 families.

Interestingly, although the population of the area has roughly halved in the last 150 years from around 300 to the present 150ish, the number of houses has hovered around the 50 to 60 mark. Families were bigger, with the larger households including labourers and other servants.

Dottack’s (or Dotach’s)  - This name is from the nickname of the inhabitant of the ruin in the corner of the field behind the dairy (Dottack’s Park). He was a cabinetmaker. The word may refer to burning something. NG851341

- This name is from the nickname of the inhabitant of the ruin in the corner of the field behind the dairy (Dottack’s Park). He was a cabinetmaker. The word may refer to burning something. NG851341

The Baltic’s - Beside the Plockton road, just south of the stepping stones at Fernaig was a building, of which there is no trace now, but a flat piece of ground. There is a ruin marked on this site on the first edition OS map. The nickname of the people who lived there was “the Baltics”. NG843338

Achmore - The 13 buildings shown at Achmore on the 1807 estate map, do not seem to correspond to any existing buildings, with the possible exception of some at the site of Achmore farm steading. The buildings shown appear to be mostly located on the higher bit of ground to the north west of the present village, and along the road to Strome. Some ruins are still visible here, for instance at the back of the Fernaig Trust office. This building is shown on several maps, with a track leading to it from where the white houses now are in “Strath Ascaig”. This was at one time a shop. (NG855337) There seems also to be evidence of a building by a holly tree just up the hill from the cattle grid, and this may be one of the 1807 buildings. (NG857339). There are ruins of a house and fank above Achmore farm, beside the new house. Other ruins were apparently destroyed when the new main road was built. (NG858337)

The 1892 Royal Commission (Highlands & Islands) lists Achmore as having had ten tenants in 1798 (corresponding well with the 1807 map), seven in 1821, four in 1852, and by 1892 there were three, (probably at Achmore, Achbeg and Holly Croft). However, the 1841 Census lists eight people as tenants at Achmore, (as well as a teacher, a merchant and several agricultural labourers). By the time of the 1891 census there were seven houses in Achmore: two people listed as crofters, one as a farmer, and others as various agricultural workers, and a “teacher of English”. The farmer (Roderick Finlayson) had a household of 13 people. This must have been at the present Achmore farmhouse, built in 1868 (listed as having 9 windowed rooms).

“Achmore was possessed in 1852-53 by four tenants each paying £36. It is now [1892] possessed in three separate holdings, one possessed by one of the original tenants, paying a rent of £108, one by the descendent of another of the original tenants, who has a good slated house and a steading, at a rent of £27, 4s, and one by a widow who has a good slated cottage and a small croft for which she pays £5, 8s.” (1892 Royal Commission, Highlands & Islands). Could these three be Achbeg, Achmore and Holly croft?

The first school at Achmore, was built in 1872 at the time of the Education (Scotland) Act, although, as noted above, there was a teacher listed on the 1841 census. It was sited on the east side of the road, by the “Achmore” sign as you approach from the north. There are a few stones remaining. (NG857337)

From the Inverness Advertiser, January 1882:

On Tuesday last, the children attending the Achmore public school were entertained through the kindness of Mr Matheson, MP., to tea, cake, confections, fruit, &c. And it was interesting to see how very handsomely the room was decorated with mottoes worked in evergreens – “Welcome,” “Thanks,” “Bliathna mhath ur,” and so on. Owing to ill health, which every one sincerely regrets, Mr Kenneth Matheson of Ardross was unable to be present, but Mr Phillips, who acted in his stead, gave the children a hearty, kindly, friendly speech – very sort, pithy, and to the point – in which he encouraged them to go on, earnestly availing themselves of the advantages they enjoyed in having such an admirable teacher as Mr Macgillivray, who succeeded other good masters; and in the event of their doing their work well, he (Mr Phillips) had no doubt that in another year Mr Kenneth Matheson, and perhaps the young ladies, if the weather should be good, would be present to entertain them. Such bursts of applause ensued! Then there was a dance, which showed that the bairns must have inherited the gift of Taglioni, for untaught in the science as they were they “stepped” well!

Marie Taglioni (1804 –1884) was a famous Italian/Swedish ballerina of the Romantic ballet era, a central figure in the history of European dance.

Glen Udalain - There are said to have been settlements in Glen Udalain, and there are some ancient remains west of the dam loch (see the section on prehistory). There are also ruins of an old settlement in the forestry plantation at the extreme east end of South Strome Forest, and two cooking pots were brought up near there, in forestry ploughing in about 1971 (NG927334).

Ardnarff - The population of Ardnarff in 1841 was 64, but there are now only two households. There are ruins around the present houses (one of which was a linesman’s house, built at the time of the railway), and there are also ruins in the forestry plantation above the road.

Imair - This was an important site for a branch of the clan Matheson, and there are ruins there. NG896367

We might tend to think of the relatively high turnover of people through the area occurring in recent years as not characteristic of past times, but the old census returns show a high turnover in the 19th century. There has been a lot of incomers and outgoers, migrant and temporary workers, for a long time. People have come here for work on the railway, the hotel, in forestry and fishing, among other things, and people have left as opportunities waned. The 1901 census records all residents as bilingual, except 4 old people and 2 young children. A similar story comes from the 1891 census, with only 2 families without English.

Isaac Lillingston - In 1831 Sir Hugh Innes died , and Lochalsh was inherited by his niece, whose husband Captain Isaac Lillingston RN became proprietor of Lochalsh. He was apparently in the habit of sailing up and down Loch Alsh in his yacht, stopping merchant vessels, and presenting the crews with copies of the Bible. He continued the evictions started by Sir Hugh Innes, and financed emigrations.

During the potato famine in Ireland potatoes were exported from the area, and barrels are said to have returned with Irish soil, used to improve the land, some around Holly Croft. In the mid 19th century the Highlands also suffered famine resulting from potato blight, and this increased the emigrations.

Alexander Matheson - In 1851 Sir Alexander Matheson purchased Lochalsh, together with Eilean Donan for £120,000, regaining old Matheson land, and adding to his already huge landholding. In 1866 he built Duncraig Castle. Matheson was also a main mover and financier of the Dingwall and Skye railway, part of which was built through his land. He died in 1886, leaving Lochalsh to Sir Kenneth Matheson, who was an absentee landowner.

Old Dykes, Ditches and Fences

The history of the area is illustrated on the ground, in the dykes and fences. The oldest walls may only be evident now as a ridge in the ground, and some of these are marked on the 1807 map. Examples are across the saddle of Craig Mhaol, and the field boundary about half way between Achnacraig and Ascaig cottage (alongside the wall). Another is across the field on your right, coming out of the north side of Achmore.

In the 19th century there were many agricultural improvements, which have appeared on the map by the time of the 1st edition Ordinance Survey map of 1875. These include drainage ditches and burn re-alignments around Braeintra,  (some of which are stone lined), and iron fence posts leaded into stones. “Galloway” dykes also date from this period. These are stone walls of a single stone thickness, a style brought by the border shepherds who came with the sheep at the time of the clearances. The theory is that the sheep won’t jump them if they can see through the gaps. Examples of these are along the back of Dottack’s park (the field behind the dairy), and some of the walls up the Glen.

(some of which are stone lined), and iron fence posts leaded into stones. “Galloway” dykes also date from this period. These are stone walls of a single stone thickness, a style brought by the border shepherds who came with the sheep at the time of the clearances. The theory is that the sheep won’t jump them if they can see through the gaps. Examples of these are along the back of Dottack’s park (the field behind the dairy), and some of the walls up the Glen.

Sites of old illicit stills - There were historically two known sites where whisky was distilled, one near the old fank (NG878326), now in the plantation up the glen, and the other on a small flat area of ground above the eastern end of the croft land at Portachullin (NG852347?). There was a government reward for information leading to discovery of these places, and the story goes that when the distilling equipment was damaged or no longer usable, the local officer would be informed of its location, and the reward collected used for a replacement.

Trees

Many trees were planted by the Matheson family in the later half of the 19th century, mostly around Duncraig, but there were also some along roadsides. Strome Wood was also planted, and there are some old Scots pines and larches remaining from this period along the railway. Forester Murdo MacRae and his labourer Alexander MacKay are recorded on the 1901 census, living in Portachullin. The Mathesons also had planted the beech hedge on the Fernaig road, which has not, according to the sale particulars of 1998, been cut since 1918. Most of the hawthorn in the area probably have origins in this time as hedges were planted around some fields. Some of the Fernaig oaks may have been planted, but many are older than this, and there is woodland here on the 1807 map. They seem likely to be of natural origin.

Roads

In 1813 the Lochalsh road (from Strome to Kyleakin Ferry) was completed. This was linked with the road to Strome Ferry from Dingwall (through Lochcarron), which was completed in 1819. There were tracks and paths throughout the area before this, but most were probably for foot traffic, although it may have been possible to get a cart down some. Many of the remains of these are visible, such as above the railway in Strome Wood, where the path cutting is quite substantial in places. Other examples are the bealach track between Achmore and Strome Ferry, running up from the cattle grid as you leave Achmore, and another, more difficult to locate, runs from Tigh Mhuillin around the hill towards Auchtertyre about a quarter of a mile above the present road.

The Railway

In 1870 the railway from Dingwall to Strome Ferry was completed.

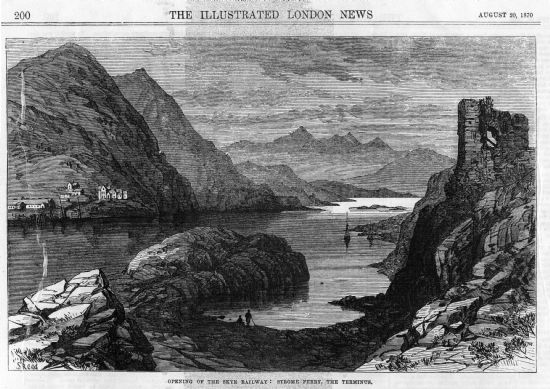

Extracts from the Illustrated London News, 20th August 1870

“Opening of the Skye Railway: Strome Ferry, The Terminus” from the Illustrated London News, 20th August 1870. “…a view of the terminus and Strome Ferry taken from the ruined castle of Strome, a building so old that it’s origin is unknown. The modern residence overlooking the sea, half way down Loch Carron , is the new castle of Duncraig, just built by the chairman of the Skye Railway Company, Alexander Matheson, Esq., member for the county of Ross, to whose indomitable perseverance, it may be said without flattery, is due the fact that this line of railway is in existence.”

“The gauge is the same as that used in England, so that, the line being unbroken, it is practicable to travel from Euston-square or King’s-cross to Strome Ferry without change of carriage, and at so little cost of time that one may dine late in London to-day and t-morrow sup in in full view of the islands of the Hebrides”

“It happened repeatedly during the formation of the railway that the navvies had to drop work, being ignorant of the local custom, on days when the atmosphere is favourable to the lively labours of the midges, of veiling the neck and face, leaving only small loopholes from which to look out. We are glad to see large squads of men at work raising embankments and constructing drains along the river side. These, we trust, will have the effect of diminishing the pest of midges, which at present is positively a curse on the country.”

“ The last few miles of the journey are literally on the waters brink – space to lay the rails has been scarped out of the rock, and from the carriage window we look down into fathoms of the most exquisite green , in which long masses of sea-ware from the side with every motion of the water.”

“…two powerful steamers run in connection with the trains, one daily to and from Portree,; the other three times a week to Stornoway, the chief town of the Lews. In anticipation of the increased traffic, a large hotel has been erected at Strome, or, rather, an addition has been made to the old one three or four times it’s original size, and including a spacious public-room, 42 ft. in length, from which there are magnificent views on every side.”

Before the railway was built, Strome Ferry was a far less significant place, with a population in 1841 of 24 – five families. By the 1891 census when it was a busy railway terminus and port, the population was 72, with 15 houses. Where there were a few fishermen and a postman, there was now an engine driver, blacksmith, fireman, post master, police constable, tailor, many porters, clerks and hotel staff, as well as shepherds and fishermen.

The railway was extended to Kyle in 1898.

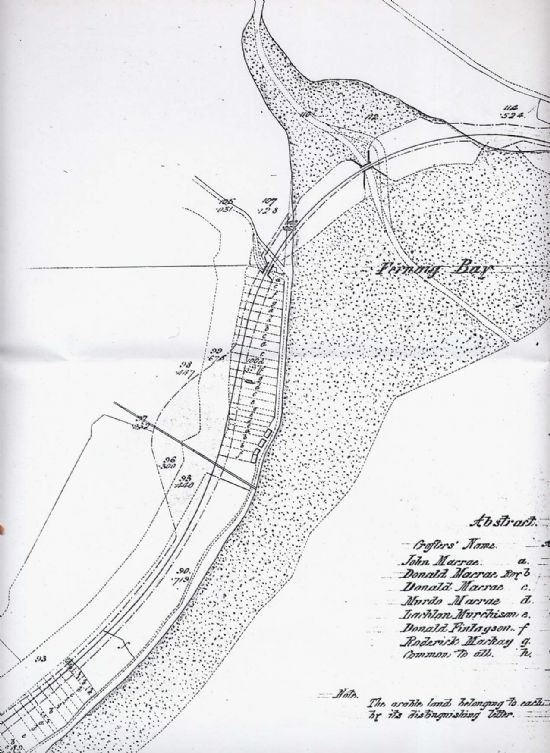

Part of the plans for the railway extension, showing the new embankment and bridges at Fernaig and some of the crofting strips which the railway was built through

Train on Fernaig Bridge